The University of Texas at Austin Athletics

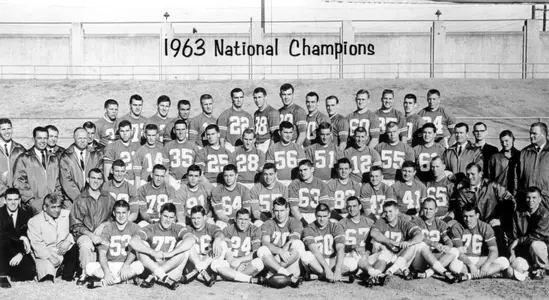

Bill Little commentary: The 1963 National Championship (Part 1)

08.29.2023 | Football

Texas Football's quest for a National Championship followed a star-crossed path.

Editor's note: This season marks the 60th anniversary of Texas Football's first National Championship. As we prepare to honor the 1963 National Championship Game at this week's game versus Rice, we're sharing part one of two-part excerpt detailing that magical season from "Stadium Stories: Texas Longhorns" by Bill Little, published by Globe Pequot. (You can read Part 2 here)

It was battleship gray, the door to the old press box elevator in the west side of Memorial Stadium, and fewer than five of us had keys to the solid padlock which guarded the door.

The elevator was hand-operated, and it stopped at the ground floor and at two of the three levels of the long concrete structure which sat atop the single level stadium. The only entrance, other than the elevator, was a single door at the north end, which exited into the top row of the stands filled with wooden seats.

Except on game days, the door was barred from the inside.

On game days, the stadium buzzed with excitement. But if you had a key on a moonlit night and you wanted a place to show your date the stars and the lights of the city, you could ride that elevator up and no one, not Darrell Royal or God Almighty--and no one was sure they weren't the same--could make it come down.

In other words, in the autumn of 1963, it seemed the safest place on earth.

That press box and the Tower were the tallest buildings on campus. There was no Jester Center, no LBJ Library.

The "Moonlight Tower" which stood on the northeast corner of the stadium cast a glow over the quirky baseball field across the street to the north, and over the wooden roof of the tennis courts which were located on the northwest corner of the stadium.

And on the field below, with a black cinder track surrounding it, a dream came true that fall, that fateful fall of 1963, when all of our lives would change, and nothing would ever seem safe again.

Texas' quest for a national championship in college football had followed a star-crossed path. For years it seemed that the Longhorns and The University were riding on a great merry-go-round, and each time they reached for the gold ring, it somehow eluded them.

A couple of their Southwest Conference brethren -- TCU in 1938 and Texas A&M in 1939 -- had earned the honor in the years since the Associated Press first began its poll in 1936. A loss to the Longhorns in 1940 even knocked the Aggies out of a second title.

The 1941 team, which was featured on the cover of Life Magazine as the best team in college football, had fallen from contention with a late season tie and a loss.

Texas would produce top ten rankings four times in the eight year period from 1945 through 1952, but it wasn't until Darrell Royal's third team finished ranked No. 4 in 1959 that UT returned to the national landscape.

All that appeared to change in 1961. Royal's first SWC championship club was a powerhouse. With an innovative offense called "the flip flop" because the offensive line and wingback would flip sides so as to simplify and maximize running plays, Texas steamrolled its opponents.

In a day of single platoon football, Royal effectively used three different teams, and most folks thought his third team backfield could play for anybody. The starting backfield featured all-American running back James Saxton, and Texas averaged over thirty points a game and yielded a scant fifty-nine points during the entire regular season.

On November 4, the Longhorns shut out SMU in Dallas, and the results of the weekend left Texas ranked No. 1 for the first time in twenty years. Two weeks later, however, the carousel of dreams would turn into a nightmare. In a stunning 6-0 shutout in Austin, a TCU team which would finish 2-4-1 in league play and 3-5-2 overall ended the quest. Texas would go on to win the first of Royal's eleven Southwest Conference titles, and would beat Ole Miss in the Cotton Bowl. The 10-1 finish, the school's best since 1947, netted a No. 3 national ranking

Texas was right back in the hunt in 1962. Despite the tragic death of a player due to heat exhaustion on first day of fall practice, the Longhorns opened with five straight victories. They were never ranked lower than No. 3, and by the Arkansas game on October 20, they had moved to No. 1. In one of the most dramatic games ever in the stadium in Austin, the Horns drove eighty yards to score the game's only touchdown with thirty-six seconds remaining in a 7-3 victory over the No. 7 ranked Razorbacks. A defining goal-line stand, led by linebackers Pat Culpepper and Johnny Treadwell, had caused a fumble which Texas recovered midway through the third quarter.

A week later, everything would change.

It was an unreal feeling that night when Rice played Texas in Houston. There was a murmur in the crowd before the game, and the whispers were not about football. The humidity seemed to hang, as it can in Houston, and it almost seems there is a ghostly mist that hangs even now as the memory returns.

On the football field, Texas was No. 1. The Longhorns had made sure of that with that 7-3 comeback win over Arkansas the week before.

But there was an eerie reality that night in Rice Stadium, as 70,000 people stood, their hearts pounding a rhythm, and their voices raised in a powerful singing of the National Anthem.

Those who were there will tell you that until perhaps the patriotic swell which accompanied the events of 9/11 and the War in Iraq, they had never -- before or since -- heard the National Anthem sung so proudly and defiantly.

Since Tommy Ford plowed over for that winning touchdown in the Arkansas game, football euphoria had reigned in Austin.

Two days later, the real showdown came.

Early in October, when Texas was busy winning football games, the Soviet Union, under Nikita Kruschev, had moved 20,000 crack battle troops, forty intermediate ballistic missiles, and forty bombers capable of carrying nuclear warheads into Cuba, less than ninety miles from Florida.

On Monday, President Kennedy ordered a blockade of Cuba, and by the time Rice played Texas, the world had edged closer and closer to World War III.

Historians will say that it probably was -- at least to our knowledge -- the closest the world has come to nuclear war.

Four hundred thousand United States troops were on maximum alert. Weapons of war were loaded aboard ships and planes. Somehow, a football game that risked a No. 1 ranking didn't seem important.

What was important, however, was a nation's pride. That is why they sang.

The game itself might as well have been played in the Twilight Zone. Rice Stadium had always been a tough place for Texas to play before the recent domination, but that year was beyond comprehension.

No one gave the Owls much chance, but as would happen often with the Owls' venerable coach Jess Neely, he had whipped "his boys" to a fever pitch to play Texas. The Longhorns never were able to get back up after the incredible "high" from the win over Arkansas. Texas trailed early, 7-0, but scored twice to make it 14-7.

Rice tied it, 14-14, and on a night when nobody appeared to want to be there, that's the way it ended. Texas would go on to an unbeaten regular season and the nation's No. 4 final ranking. Rice would finish the year at 2-6-2, but the tie kept the Longhorns from a national title.

The game was only a brief distraction from the fear of the greater conflict, a conflict that threatened life as we knew it.

But on Sunday -- the next day -- the Good Guys won.

The Soviet Union relented and began removing its troops and dismantling the missiles. President Kennedy gave the order for the United States Armed Forces to stand down. The danger of the missiles of October was over.

That, however, was only a harbinger of the mixture of fate that would manifest itself in the lives of the young men of Texas football in the early 1960s.

What 1961 and 1962 had done was create a strong winning tradition, and with an all-star cast, Royal and his staff were ready for 1963. The Horns began the season ranked No. 5. They moved to No. 4 the second week, No. 3 the third week and by the fourth week of the season, they were No. 2 as they headed for Dallas and the annual meeting with Oklahoma.

Since Royal's first season of 1957, the Longhorns had not lost to the Sooners, but the national voters, the writers and the coaches, had installed No. 1-ranked Oklahoma as a favorite. Joe Don Looney, the Sooners' star running back, had even challenged the biggest name on the Texas defense, Outland Trophy winner Scott Appleton, by saying, "Appleton's tough, but he ain't met the Big Red yet." Neither, he would find, had he met Appleton.

The annual showdown in Dallas was the biggest game, but it came on a weekend of irony. The Friday night before UT and OU met, SMU knocked off the power of the East, Navy, and Heisman Trophy winner Roger Staubach, in the Cotton Bowl Stadium.

Then the next day, No. 2 met No. 1.

It was an execution of precision. With Carlisle operating the Royal Winged-T offense to perfection and the defense hammering the Sooners, Texas won 28-7. A sportswriter from St. Louis perhaps told the story best when he wrote in his lead, "Who's No. 1? It is Texas, podner, and smile when you say that."

Texas then began the improbable gauntlet of carrying the mantle of the nation's No. 1 team for six long weeks. It made it through tough wins over Arkansas (17-13), Rice (10-6), SMU (17-12), Baylor (7-0), TCU (17-0) and Texas A&M (15-13).

The Baylor game, matching the unbeaten Horns against a Baylor team led by Don Trull and Lawrence Elkins, had been the best showdown in years in the Southwest Conference, with a Duke Carlisle interception of a late sure touchdown saving the Longhorns' victory.

Texas beat TCU, 17-0, the next week, and looked forward to an open date on November 23 before finishing the regular season at Texas A&M.

Darrell Royal was standing in his bedroom, tying his tie, getting ready for the events of the afternoon.

It was Friday, Nov. 22.