The University of Texas at Austin Athletics

Bill Little commentary: Down to the bone

08.27.2008 | Football

Aug. 27, 2008

Bill Little, Texas Media Relations

(NOTE: Forty years ago, the Texas Longhorns were preparing to open the 1968 football season against the University of Houston, which was then a power as an independent in college football, and a significant threat to football supremacy in a state which for more than half a century had been dominated by The Southwest Conference. Texas was coming off of three consecutive seasons in which the Longhorns had lost four games in each. Darrell Royal had given his backfield coach, Emory Bellard, an assignment to create an offense that would put a talented stable of runners to their best use. Here, reprinted from the book, "Stadium Stories -- Texas Longhorns" by Bill Little, is an excerpt from a chapter that tells the story of that pivotal change in Longhorn history, and in the history of college football.)

Emory Bellard sat in his office, down the narrow, eggshell-white corridor that was part of an annex linking old Gregory Gymnasium with a recreational facility for students. There were two exit doors, one at the glassed-in front of the two-story building, and the other at the end of the hall.

Summer in 1968 was a time for football coaches to relax, and to prepare for the upcoming season. Most of Bellard's cohorts on Darrell Royal's staff were either on vacation or had finished their work in the morning and were spending the afternoon at the golf course at old Austin Country Club.

Texas football had taken a sabbatical from the elite of the college ranks in the three years before. From the time Tommy Nobis and Royal's 1964 team had beaten Joe Namath and Alabama in the first night bowl game, the Orange Bowl on January 1 of 1965, Longhorn football had leveled to average. Three seasons of 6-4, 7-4 and 6-4 had followed the exceptional run in the early 1960s.

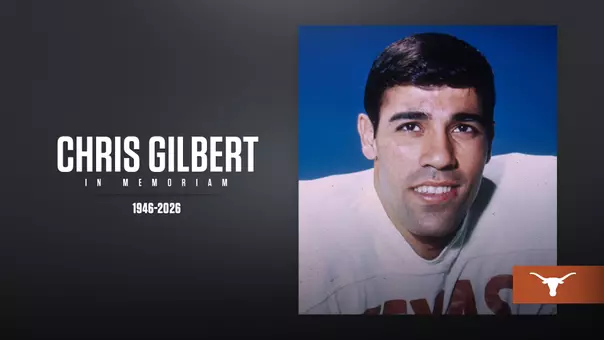

Despite an outstanding running back in future College Football Hall of Famer Chris Gilbert, the popular "I" formation with a single running back hadn't produced as Royal and his staff had hoped. So with the coming of the 1968 season, and the influx of a highly-touted freshman class who would be sophomores (this was before freshmen were eligible to play on the varsity), Royal had made a switch in coaching duties.

Bellard, who had joined the staff only a season before after a successful career in Texas high school coaching at San Angelo and Breckenridge, was the new offensive backfield coach.

Bellard had gone to Royal with the idea of switching to the Veer, an option offense that had been made popular in the southwest at the University of Houston. As the Longhorns had gone through spring training, they had returned to the Winged-T formation, which Royal had used so successfully during the early part of the decade.

So, as the summer began, the on-going question was, who was going to play fullback, the veteran Ted Koy, or the sensational sophomore newcomer Steve Worster? With Gilbert a fixture at running back, even in the two-back set of the Veer formation, only one of the other two could play.

And that is how, on that summer afternoon, the conversation began.

"So, who are you going to play, Koy or Worster?" the question was asked. Bellard took a draw on his ever-present pipe, cocked his chair a little behind the desk that faced the door, and said, "What if we play them both?" He took out a yellow pad and drew four circles in a shape resembling the letter "Y."

"Bradley," he said, referring to heralded quarterback Bill Bradley, as he pointed to the bottom of the picture. "Worster," he said, indicating a position at the juncture behind the quarterback. "Koy", he said as he dotted the right side, "and Gilbert," indicating the left halfback.

Royal had told Bellard he wanted a formation that would be balanced, and that, unlike the Veer which was a two back set, would employ a "triple" option with a lead blocker. On summer mornings, Bellard would set up the alignments inside the old gymnasium next to the offices, using volunteers from the athletics staff as players.

As fall drills began, the formation was kept under wraps. Ironically, Texas opened the season that year against Houston. It was only the second meeting of the two. The Longhorns had won easily in 1953, but the Cougars had established themselves as an independent power that was demanding respect from the old guard Southwest Conference.

A packed house of more than 66,000 overflowed Texas Memorial Stadium for the game, which ended in a 20-20 tie. The debut of the new formation didn't exactly shock the football world.

A week later, Texas headed to Texas Tech for its first conference game, and found itself trailing 21-0 in the first half. It was at that point that Royal made the first of a series of moves that would change the face of his offense and the face of college football, for that matter.

Bill Bradley was the most celebrated athlete in Texas in the mid-1960s. He was a football quarterback, a baseball player, could throw with either hand and could punt with either foot. He was a senior, and when Royal unveiled the new formation, he thought that Bradley's running ability would make him perfect as the quarterback who would pull the trigger.

But trailing in Lubbock, Royal made one of the hardest decisions of his coaching career. He pulled Bradley and inserted a little-known junior named James Street.

A signal caller from Longview, Street had been an all-Southwest Conference pitcher in baseball the spring before, but no one could have expected what was about to happen.

Street brought Texas back to within striking distance of the Raiders, closing the gap to 28-22 before Tech eventually won, 31-22.

Back home in Austin, the staff met to adjust where the players lined up in the new formation. In a debate that was won by offensive line coach Willie Zapalac, the fullback position alignment was adjusted. Worster, who had been lined up only a yard behind the quarterback in the original formation, was moved back two full steps so he could better see the holes the line had created as the play developed.

Against Oklahoma State the next week, Texas won, 31-3. Nobody realized it at the time, but that would be the start of something very big. With Street as the signal caller, that win was the first of 30 straight victories, the most in the NCAA since Oklahoma had set a national record in the 1950s, and a string that held as the nation's best for more than 30 years.

While the Oklahoma State game started the streak, the Oklahoma game the next week would become known as, "The Game That Made the Wishbone."

Texas was 1-1-1 as it headed to Dallas to play the Sooners, and with only 2:37 remaining in the game, Street and Royal's new offense was at their own 15-yard line, trailing 20-19. A legend was about to be born.

Street hooked up with tight end Deryl Comer for pass completions of 18, 21 and 13 yards, and then connected with Bradley, who had moved to split end after the Tech game, for 10 yards to the Oklahoma 21-yard line. Only 55 seconds remained as Worster crashed through a big hole to the seven.

On the sidelines, assistant coach R. M. Patterson corralled a wide-eyed Happy Feller, his sophomore field goal kicker, and told him that if the Longhorns didn't score a touchdown on the next play, he was going to have to hurry out and kick, because Texas was out of timeouts.

While Texas was struggling on the field in the mid-1960s, the recruiting season of 1967 had netted the most successful recruiting haul in Southwest Conference history. The linchpin of the group was Steve Worster, a powerful running back from Bridge City. The recruiting class would forever be known as "The Worster Crowd."

With time running out at the Oklahoma 7-yard line, James Street handed the ball to Steve Worster. Two Sooners tried to stop him, but the bruising fullback who was on his way to stardom dragged them with him as he dived into the end zone. Only 39 seconds remained. Texas won, 26-20. The next week the Longhorns pounded Arkansas.

In one of his post-game meetings with the sportswriters at the Villa Capri Motor Hotel (which stood where the UT indoor practice facility is located today) following the game, a writer asked Royal what he called the new offense.

"I don't know," he said. "What do you guys think?"

Mickey Herskowitz of the Houston Post followed several other suggestions by saying, "Well, it looks like a chicken pully-bone."

"Okay," said Royal. "The Wishbone."

The new-fangled offense would team with a solid Longhorn defense to dominate the era. Street would record the best won-loss record as a quarterback in Texas history, starting 20 games and winning all of them.

The 1968 team would finish third in the country, pounding No. 8 Tennessee, 36-13, in the Cotton Bowl. The offense had become unstoppable. Following the 20-20 tie with Houston in the season opener, Cougar coach Bill Yeoman had told the media, "I wish we had a chance to play them again." That prompted irreverent sportswriters to comment at half-time of the New Year's Day game in Dallas, "somebody call Yeoman and tell him to bring his team on up…this thing is over."